Indians, watch the US elections like an outsider

There are many ways of consuming the US elections from a distance. The most instructive among them might just be the philosopher’s perspective of it.

Yogendra Yadav :

US elections are like a wedding in the big landlord’s family in our village. It makes for a spectacle, designed to keep the entire village busy for some time. As rituals do, it brings out tensions and fissures within that family. As affairs of powerful families do, it has some fallouts for everyone, including us.

But as village elders know, we must not forget that this is not a wedding in our family. A vicarious partisanship — pro-Trump or pro-Harris — is not just misplaced, it is undignified. The foolhardiness of “Begane ki shadi me Abdulla diwana” may be redeemed by its romanticism in some other context. But in relation to a powerful family, this response is cringeworthy.

A village elder might also remind us that the US is not even our neighbour. Our sense of proximity to them is largely imagined. So is our exaggerated anxiety about what a Donald Trump or Harris administration can mean for us. That Kamala Harris shares her first name with my mother cannot make me forget that what matters most to this Kamala in relating to my country is the cold logic of geopolitics and GDP. For us, a charming Obama was not fundamentally different from a boorish Trump. For us, the POTUS is a POTUS. So, keeping a distance from this contest is not a bad idea. As they say, “hathi se na dushmani bhali, na dosti”.

This is not the family of our priests either. They may have tried preaching and exporting democracy to the world, but thanks to Trump, that posture looks more comic than ever before. Democracy in the US may be anything else, but it is no model of how to be a democracy. Looking at the US political system with any sense of awe is not just silly, it is slavish.

We are an outsider in this wedding. An inconsequential outsider. And that’s not a bad position to be in.

After all, the all-time classic on American politics was not written by an American nor written in English. Alex de Tocqueville, a French aristocrat who visited the US for nine months in 1831, ostensibly to study prison reforms, wrote Democracy in America, originally in French. The two volumes were translated into English in 1835 and 1840 and remain compulsory reading for any student of American democracy. Tocqueville reminds us that an outsider can throw fresh light on a familiar subject, provided the outsider is conscious of her dharma.

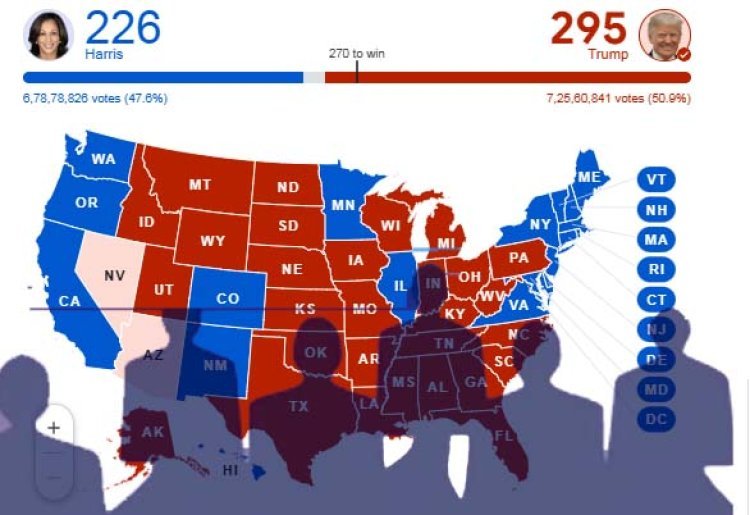

An outsider can be just a spectator. We can watch the US polls just as we consume a cricket match between South Africa and West Indies. We can turn on CNN, read NYT or The Washington Post or follow Indian media’s second-hand reporting. Election junkies like me could track the polls on fivethirtyeight.com and realandclearpolitics.com. We can indulge in the favourite Indian pastime and make a prediction. And then watch the trends in the election night coverage, the ultimate spectator sports. It’s time for pure, detached pleasure. But it is transient.

An outsider can be a voyeur. And there are many scandals to feed on in this US election. A fracas during a village wedding, not a very uncommon sight, can rip apart the carefully crafted veil of civility and superiority of the “first family”. This is what the present US election, with Trump’s verbal diarrhoea and his daily dose of lies, has done. The sight of a doddering Joe Biden as the candidate of the Democratic Party makes all our political leaders look smart and agile. And the vacuity of Harris’s glib talk assures us that thoughtlessness is not an Indian political affliction. A glimpse into the sociology of voting in the US — Black, Hispanic, Indian, Arab, White working class, White middle class, women of colour, etc — is so reassuringly reminiscent of “vote bank” politics in the Indian elections. As you follow the election campaign, you can entertain yourself with a thought experiment: How would the international media react if a Trump-like candidate, backed by an Elon Musk-like businessman, were to win an election in an African country? A voyeur-like interest in the US election gives us the power to laugh at the powerful. But it also demeans us.

An outsider can be a friend. An honest friend who is not afraid of telling the truth in your face, who is not awkward about learning from you. This is what Tocqueville was in the first half of the 19th century. He correctly anticipated that the rising force of democracy and the spirit of equality that he witnessed in the US then was going to replicate itself all over the world. We need a similar pair of eyes to watch this US election. If Tocqueville’s US was in many ways an exemplar of the rising tide of democracy, today’s US is arguably a model of how not to be a democracy.

The “electoral college” system that can defeat popular vote, the political partisanship of higher judiciary, the institutionalisation of political corruption via lobbying, the power of media conglomerates and the control of money bags are deep-rooted anti-democratic features of the American system. These structural weaknesses could be pushed under a carpet during the days of American hegemony. But the decline in its economic and political power has uncovered various tensions in society. Hence, the many paradoxes in this election. The largest support of the candidate whose only qualification is his money comes from the working class. Older non-White immigrants are being mobilised against newer non-White immigrants. The more jingoistic and visibly racist of the two candidates is trusted to bring peace. What is happening to the US is what happens to the family of the rural landlord whose declining fortune does not match its status. It turns inwards and is petty. Is this going to be the fate of entrenched democracies in the “developed” world?

Finally, we could look at this election to draw conclusions not just about the modern country called the USA but about the modern deity called democracy. What made us believe that the system of representative governance was going to give us good governance? Why did we think that popular rule would be free of popular prejudices and pettiness? How did we accept that a system of political equality was compatible with a system of political and social inequality? An outsider can be a philosopher too.